Ripping, restoring, and decompiling the factory operating system.

In this tutorial we’re going to review the memory layout of the STM32F103.

We’ll use this information and our tools to copy both the factory bootloader

and factory operating system to our development computer. We’ll finish

by opening both the bootloader and operating system in Ghidra, and

writing some early observations about how they work.

The memory layout of the STM32F103: Memory-mapped I/O

Here is what the memory layout of the STM32 looks like.

Memory addresses are represented in hexidecimal, so each digit goes 1 to 9, then A, B, C, D, E, F.

What’s really fascinating is that every part of the chip is represented as a memory address. So when we see which wires are connected to which, we will literally be reading and writing memory addresses. When we write to or read from the USB, it will be abstracted as writing to or reading from memory. As we’ll see, our entire operating system will use this abstraction over and over to communicate with the LCD screen, the keyboard buttons, and the USB module.

There are two pieces of software running on the device, the bootloader, and the operating system. The bootloader is executed first, then it finds the stored

copy of the operating system and loads it into ram.

The bootloader is located from memory address 0x0 to 0x6000, and it is mirrored at 0x08000000 to 0x08006000. Canonically, the operating

system is located starting at 0x08006000.

The bootloader is 0 to 0x6000 or 24576 bytes. That’s not too bad! We have a reasonable chance of reading and understanding what it does if we were to decompile it in Ghidra.

Each memory address stores a byte, which is made of up of two hex digits, like 0xA5, or 0x01, for example, up to 0xFF.

The addressess typically run in sequences of 2 or 4 bytes. 2 byte sequences, like 0x04 0x06 (move the value of register 0 to register 4) are usually Cortex M3 instructions. 4 byte sequences are typically either “vectors,” which means they store an address on the chip itself, or 4 byte Cortex M3 instructions.

It can be really hard to read through sequences of bytes to try to figure out which instructions are encoded, forget about whole functions. Decompilers like Ghidra or IDA load these byte sequences and display them in human-readable code so you can understand what is happening.

Ripping the bootloader, the OS, and both.

GDB can copy sectors of memory from your MPK2 to your local filesystem using the dump command. We’ve made a script in the util/ folder of the Open Klave source tree to make this easier: “copy_os_from_device.sh”.

dump binary memory bootloader.bin 0 0x6000

Will dump the bootloader to a bin file. Note you can also dump it to an ihex file format, which we’ll discuss later.

Make sure you keep this backup file in a safe place. It is essential to be able to quickly and cleanly load and wipe the chip memory.

dump binary memory mpk2os.bin 0x08006000 0x08033fff

Let’s be safe and also dump the os in the ihex format so we can reload it using the bootloader

dump ihex memory mpk2os.ihex 0x08006000 0x08033fff

Now shockingly enough, this bare ihex dump is sufficient to completely restore the operating system if you bork it during development.

The bootloader has a built-in recovery mode which receives ihex as a sysex message and rerwrites the flash over usb.

Use the factory bootloader to load the operating system back on to the keyboard

Now that we’ve copied the OS to our development computer, let’s load it back onto the device. The factory bootloader does a lot with very little. It has a bare USB driver that is able to accept new software in the form of MIDI Sysex commands from the development computer. Note, if you are using these tutorials to learn about reverse engineering and bare metal OS development generally, you could always just flash an OS back your device using GDB. But throughout Open Klave we rely on the factory bootloader, because it can be accessed using just a USB cable, so non-developers can use Open Klave on their machine without a JTAG probe.

Earlier, we ripped the operating system and saved it as IHex, or Intel Hex. IHex is an interesting binary protocol. It is a sequence of records in plaintext, specifying a start address on the chip, and then data to copy to that address. It is coded in ASCII to be human readable. So for example, if you wanted to copy the byte ‘0xE3’ to the device, that would be represented in ihex as 0x69 0x51, the hexidecimal representations of ‘e’ and ‘3’. It takes 2n bytes to convey n bytes of information in the format.

Conveniently, this format is also byte-compatible with Midi Sysex. So basically, you can take a binary written in ihex, and just add F0 and the machine status bytes at the top of the message, and F7 at the end, and the bootloader will understand and copy it to the device. You can even break up ihex messages into chunks for faster transmission.

Read through the code in ‘util/flash_os.py’, and use it to copy the operating system back on the device. First, turn the power off. Then, while holding the ‘Push to Enter’ button, turn the power back on. Then run the script to copy the OS to the chip.

Decompile the factory bootloader in Ghidra

We have now copied the bootloader and operating system to our development computer, and used the factory bootloader to reload the operating system back onto the keyboard just using the USB cable. Let’s take a moment and see if we can learn anything about the bootloader code.

Open Ghidra, and import the bootloader ihex file. The format is Intel Hex, and the language should be Arm Cortex 32-bit little endian. Do not analyze it yet. We need to make a few adjustments to see it in proper context. First, you should install the SVD-loader plugin for Ghidra from leveldown security. This allows you to take an SVD file, which maps memory areas to text descriptions of peripheral devices to your binary. You can find an XML description of the STM32F103 architecture in ‘util/STM32F103xx.svd.txt”, which you can load.

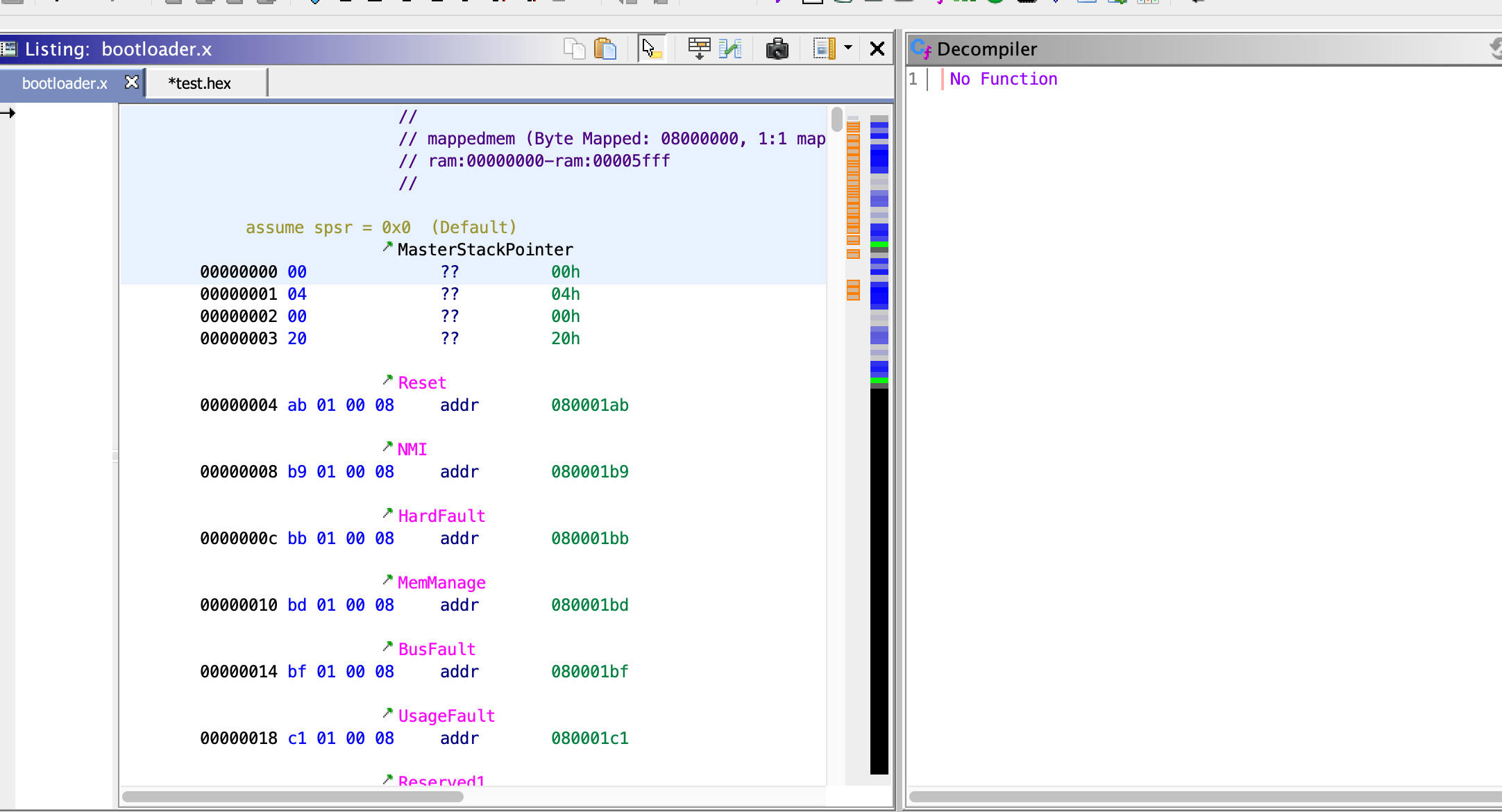

Next, we need to remap Ghidra’s memory so it is properly aligning the binary addresses with its internal description of how the STM32F103 works. Finally, open the analyzer and do all the analyses. If everything worked you should see something like this:

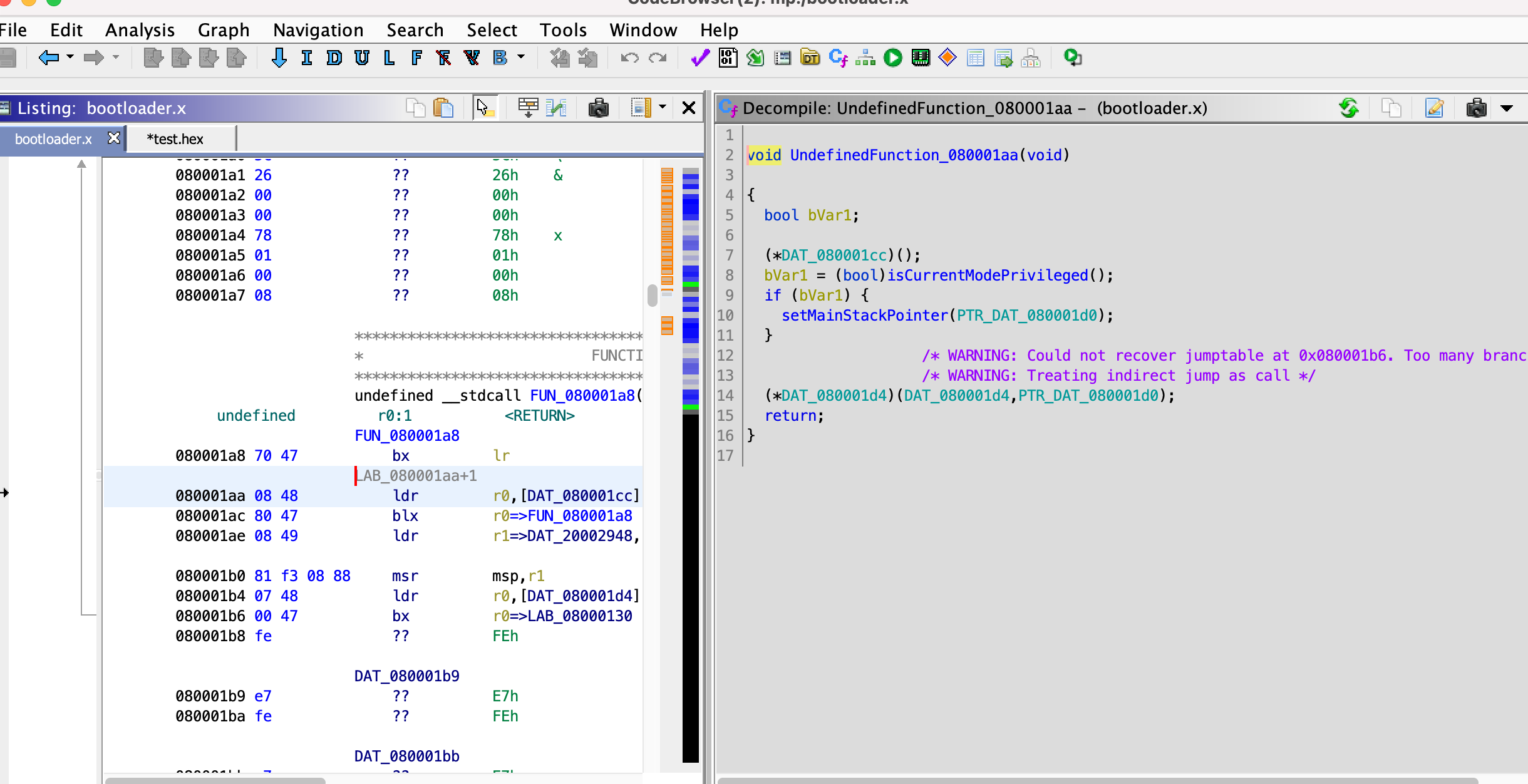

This is the ‘interrupt vector table’. It specifies 4 byte addresses that should be jumped to when different events happen on the device; for example if a timer goes off, a USB is connected, or the device is powered on. Let’s jump to the ‘reset’ vector in Ghidra. This is the entry point the bootloader goes when the device is turned on:

Playing with Ghidra: where is ihex loaded in the bootloader?

Now we’re cooking. We can start to do an educational loop: we query where a certain functionality takes place in Ghidra, and we can set a breakpoint in GDB and watch it live. Or we could set a breakpoint in GDB that happens when a value of interest changes, and write down the interesting instruction and examine it in Ghidra.

We learned above the bootloader starts a USB connection with the host computer, and then accepts ihex in the form of a stream of Sysex messages. How do we find out where it is?

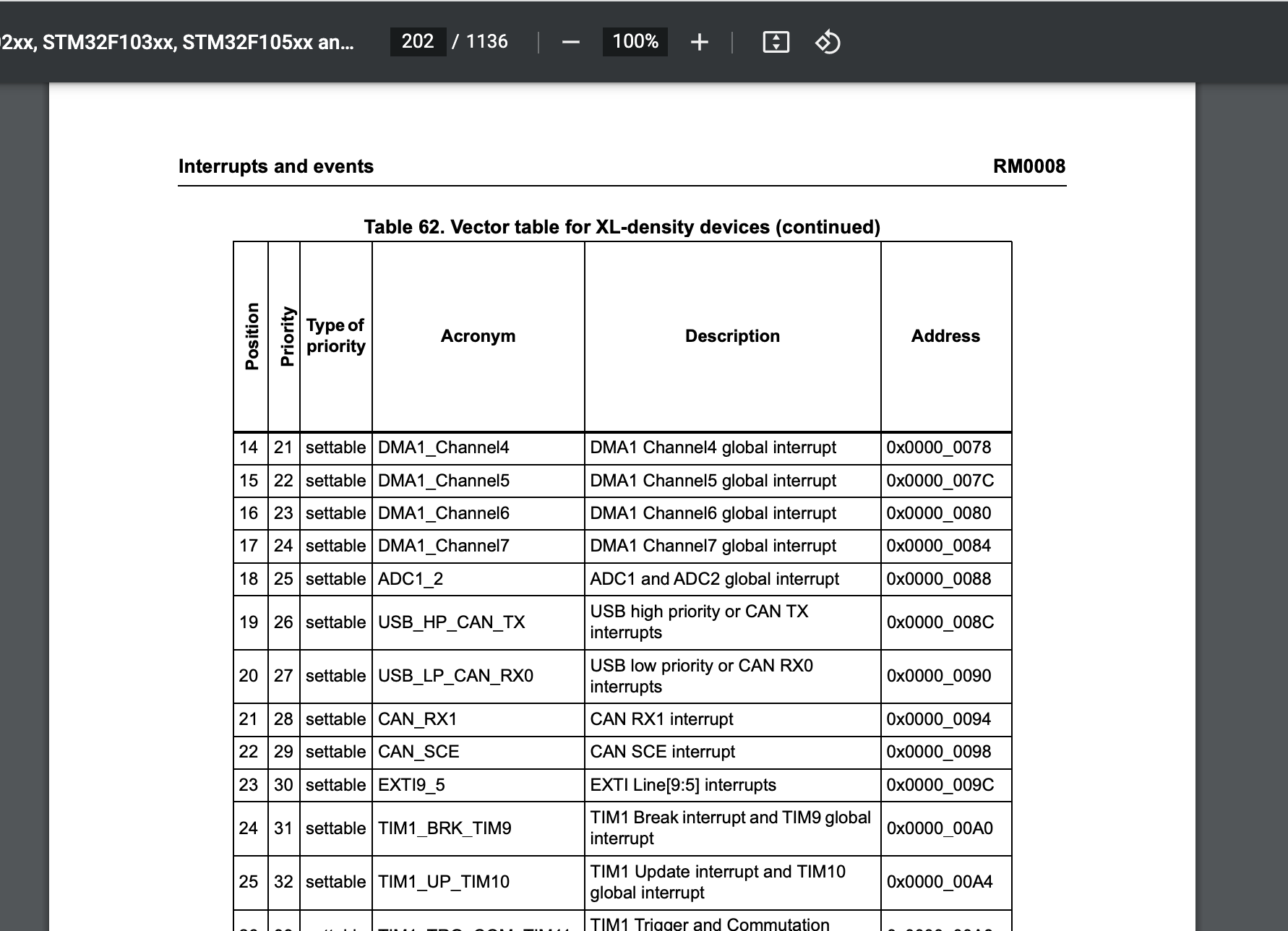

We turn to our first of several thousand trips to the STM32f103 developer manual. You can find a mirrored copy here. I cannot overstate the importance of reading this manual - literally every single thing you could ever want to know about keyboard’s chip is explained in excruciating detail. For these tutorials, we’ll start by skimming just a bit at a time when it is relevant so we can develop familiarity with it.

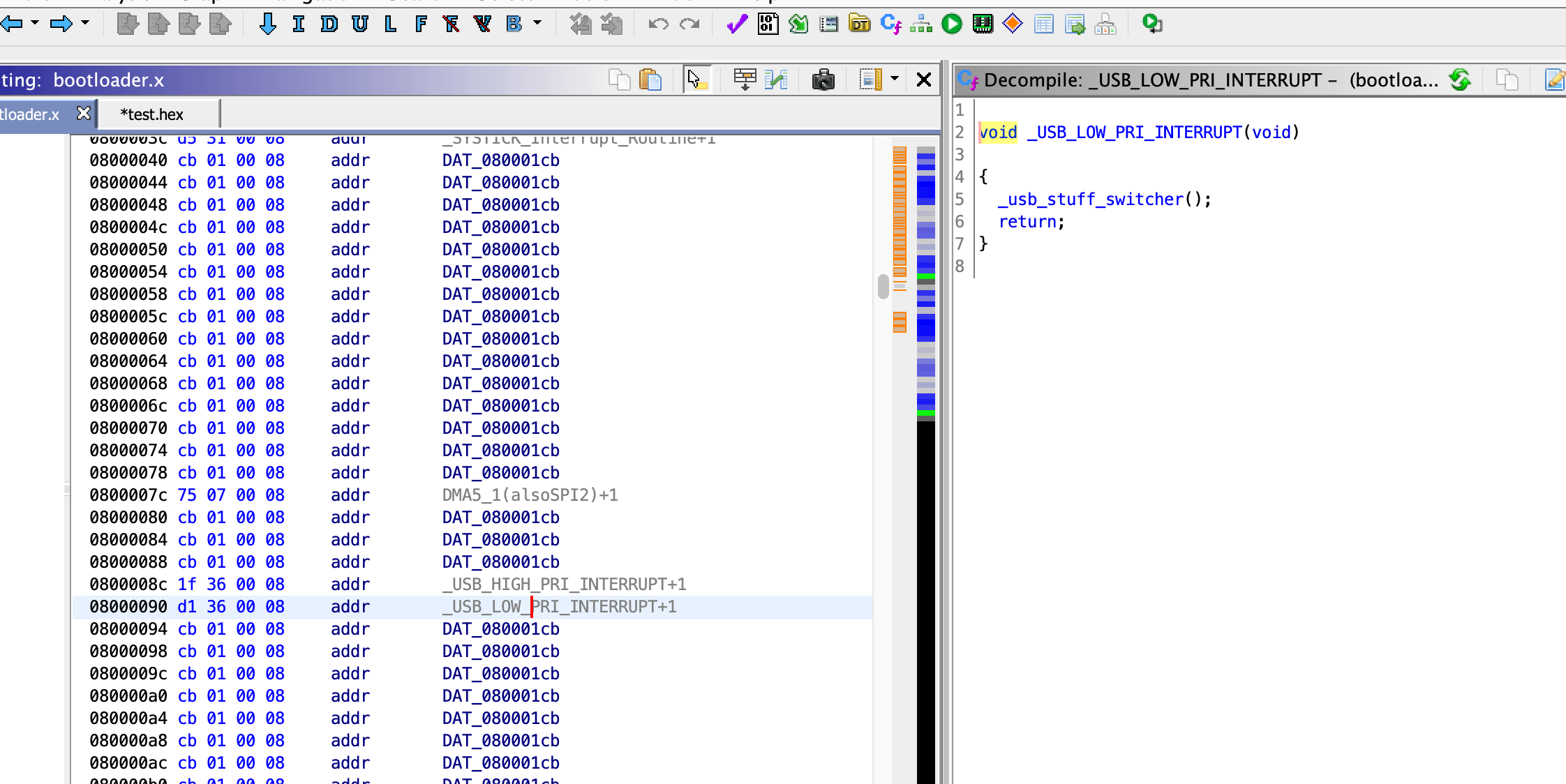

Ok so according to the manual, the interrupt routine that should be called every time there’s a USB event is at offset 0x90.

Ah! There’s a routine defined there, at address 0x080036d0. As you can see, I hand renamed these addresses and functions, which you can do too in Ghidra by right or long pressing on any address or name and clicking rename.

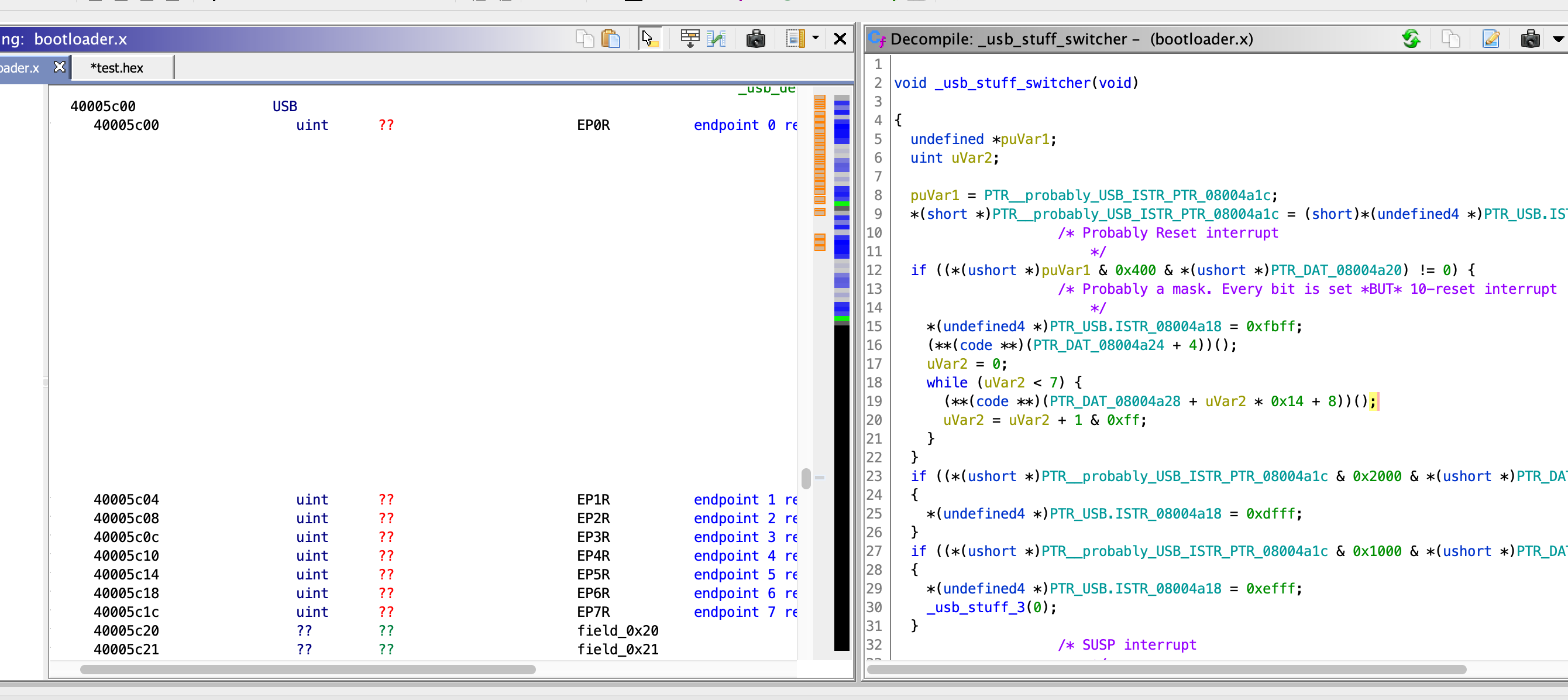

It can be very fruitful to just click through the code in Ghidra and chase different functions. This figure shows a couple of interesting things. First, we see that the SVD-loader helped define a bunch of USB registers starting at 0x40005c00. When we write our USB driver, we’ll start by examining what those registers do in the manual, and writing c pointers that point to these addresses in our operating system so we can easily manipulate them. We also see my attempts to analyze, comment, and rename the USB function in the bootloader to make sense of it.

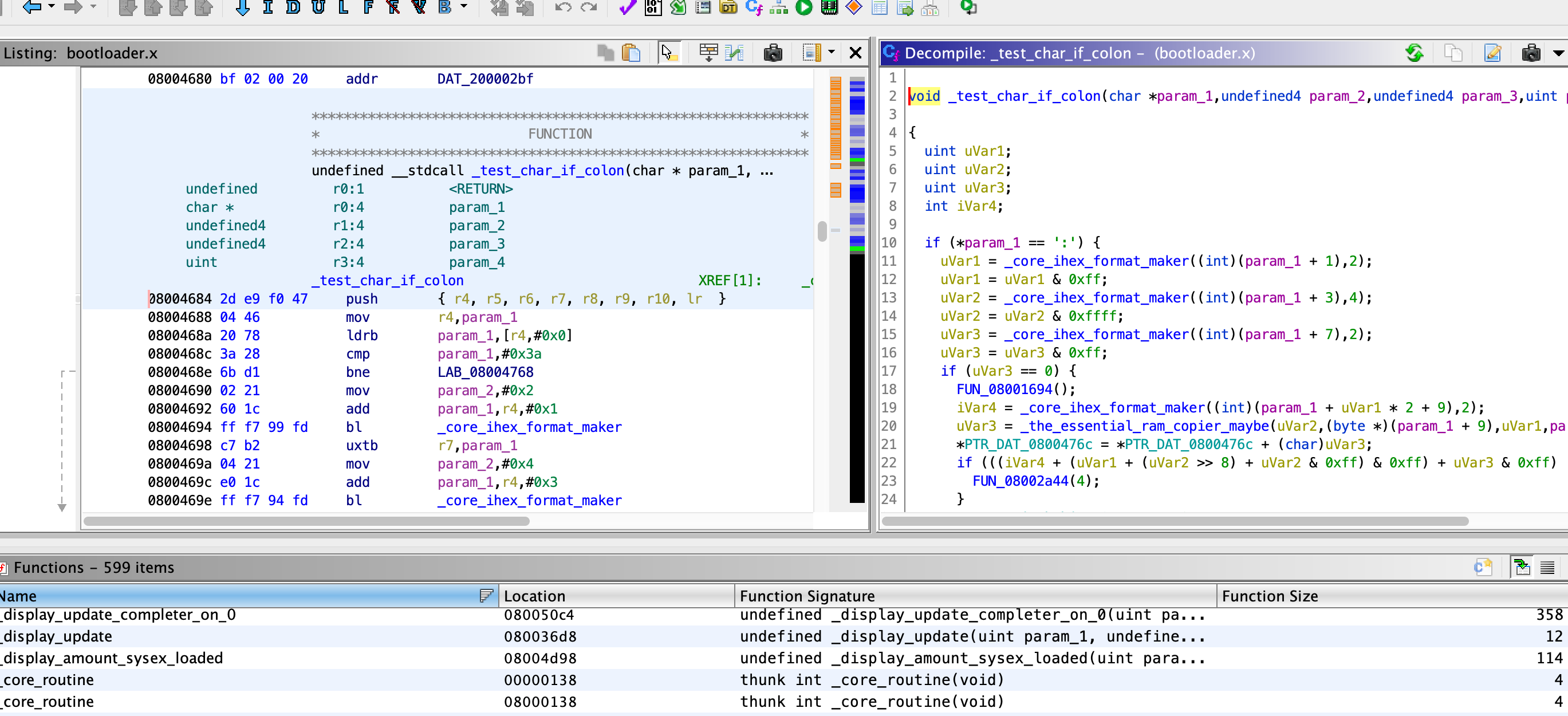

Ok now, to the ihex parsing. How on earth can we find out where it happens? One technique is to try to identify special characters that you know have to be there. For example, we know every ihex record starts with an ascii “:”, so it stands to reason the parsing routine would have to look for that, right? Or in assembly speak, there should be a routine somewhere that has to compare byte 0x3a to a value in a different register to see if they are the same. And in fact we find it. Look at the Cortex assembler instructions on the left, and how Ghidra has decompiled them into c-ish on the right.

A last obstacle: copy-protection and linker memory allocations

An annoying and interesting thing happened the first month I tried to use the factory bootloader to load early versions of Open Klave: It kept erasing it! Every time I reset the power after transmitting the OS, gone. I booted up OpenOCD, established a gdb connection using ‘target remote localhost:3333’, and had a copy of Ghidra open in the background to investigate.

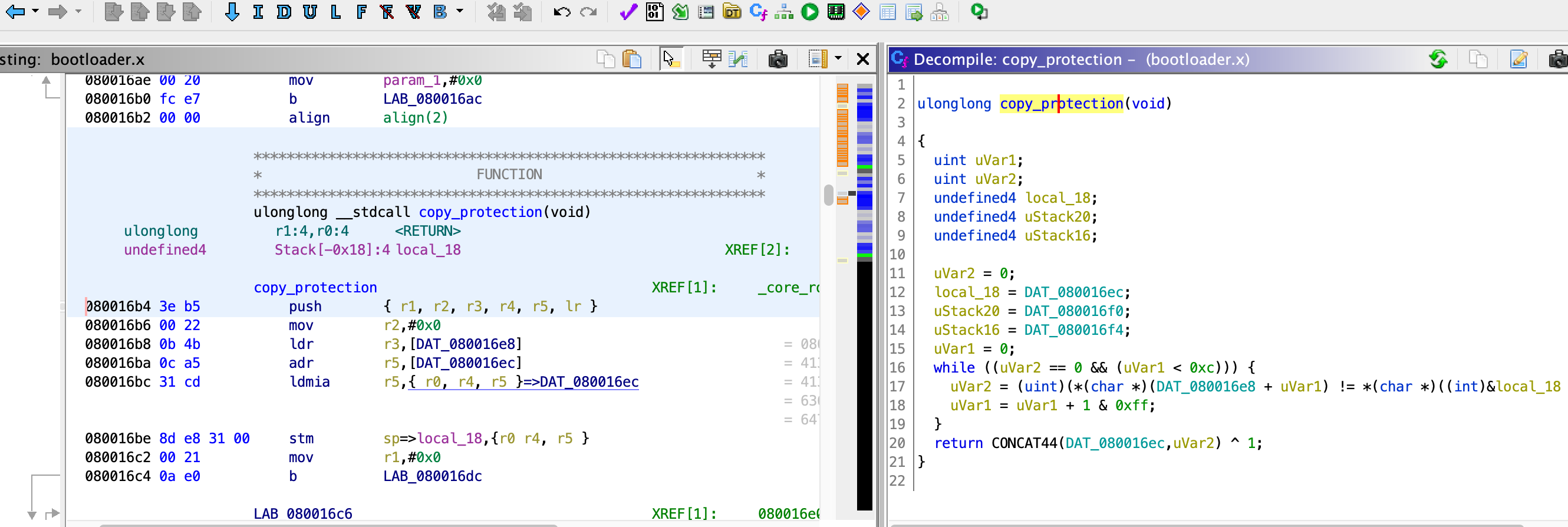

Turns out the main loop of the bootloader calls a silly function that checks an address in the operating system.

If the operating system’s address 0x08033800 doesn’t exactly spell out the string “AD4A_Richard,” the bootloader nukes it.

Quick legal aside.

As explained in the legal tutorial, many laws in the United States, including the DMCA, allow for circumventing copy protection, as well as copying, for interoperability, repair, and fair use, among other uses. See for example Lewis Galoob v. Nintendo. As there is no other way for a keyboard owner to maintain and interface with the keyboard besides storing this magic string at the designated address, it’s OK. Especially given Akai’s notable historical record of refusing support for older devices, and numerous corporate bankruptcies and restructurings, a device owner has no reasonable expectation the manufacturer will continue to support the device they purchased in the future, and is entitled to make personal modifications of its operating software for their own enjoyment and use.

Solution

In your operating system code you can place something like this, from Open Klave:

// Annoying secret word that needs to go at the

// end of the binary so the default bootloader doesn't

// try to delete it.

// Stored at 0x08033800 by the linker.

char boot_secret[] __attribute__((section(".mySection"))) =

{'A','D','4','A','_','R','i','c','h','a','r','d', 0x1 , 0x0 , 0x2};

and force your linker to put that string in the exact spot in memory its required:

/* Define output sections */

SECTIONS

{

/* placing my named section at given address: */

.mySegment 0x08033800 : {KEEP(*(.mySection))}

...